A dozen kilometres from the CBD, suburban Kew unrolls beside the Yarra as a mixture of red brick middle class and the city's old money mansions. A short distance up High Street, one of the main roads East, the Boorondoora Cemetery nestles on a triangular wedge of land, surrounded by a two metre high wall.

Within the wall lies one of Melbourne's great hidden treasures: The Springthorpe Memorial.

John William Springthorpe was born in Staffordshire, England, in 1855 but his parents emigrated to Australia when he was an infant. Educated in both Sydney and Melbourne, Springthorpe studied medicine at the University of Melbourne where he garnered a number of academic distinctions.

Graduating in 1879, Springthrope worked at the Beechworth Asylum, one of the city's first mental hospitals, before moving to England. In 1881 he became the first Australian to be admitted to the Royal College of Surgeons. Moving back to Melbourne in 1883, Springthorpe combined further study with stints working at both the Alfred and Melbourne hospitals.

|

| John William Springthorpe |

A lively and vigorous man, Springthorpe's brilliance in his field could be measured by the tremendous number of projects he became involved in. Once his studies were complete, he opened a successful private practice on Collins Street and began lecturing at Melbourne university on a range of topics. In addition, he also founded the university's first school of dentistry, co-founded Victoria's first nursing association, wrote a number of well received medical textbooks, served as President of various medical boards and devoted time to a number of community programs, including assistance for single parents and disadvantaged children. He also had a fondness for art and was an avid collector.

In 1887, in the midst of all of this activity, John Springthorpe got married.

|

| Annie Springthorpe, nee Inglis. |

Annie Inglis was an attractive young woman from a well off, well connected local family. She was related to the a'Becketts and the Boyds, both prominent names in Melbourne society at the time (in the legal and artistic worlds, respectively) but had a well rounded character that belied her privileged upbringing. Intelligent, cultured and lively, yet down to earth, Annie seemed an ideal match for the energetic, brilliant young doctor.

The two fell passionately in love and were married on Australia Day, 1887. The picture of Annie displayed above was commissioned by her husband, to celebrate their nuptials. In his diary, John Springthorpe would describe his wife as, 'self sacrificing, modest, tender, true and wise.' They had three children together and were thought of as an ideal couple, deeply in love.

Life was good.

So, in some ways, the resulting tragedy seems almost inevitable.

In 1897, and aged only thirty, Annie Springthorpe died giving birth to her fourth child. Her husband was devastated.

A devout Protestant, Springthorpe turned initially to traditional forms of mourning to try and assuage his grief. He kept locks of his departed wife's hair as well as her jewelry, as tangible keepsakes. And the house he had shared with Annie, 83 Collins Street, was turned into a kind of shrine; the walls were covered with photographs and paintings of her.

None of which seemed to help. In his diary, Springthorpe despaired, 'She has come no nearer - No miracle - No farewell! No voice from beyond. Simply an icy silence.'

A practical man, and a man of considerable means by this time, Springthorpe then decided to create a grand memorial to mark Annie's grave. Harold Annear, one of Melbourne's most prominent architects, was engaged and he designed an elaborate, Greek inspired temple to this end.

|

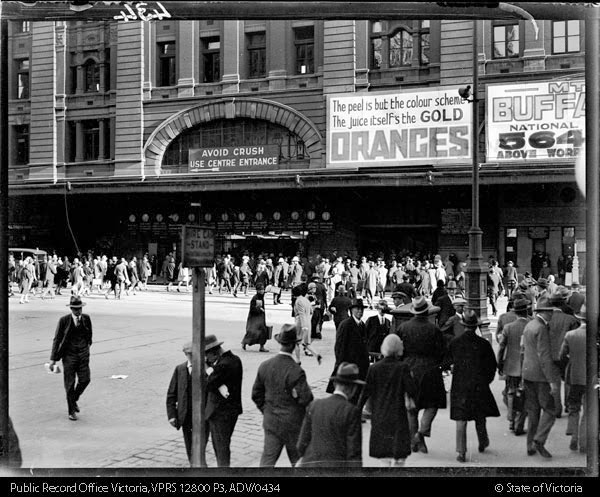

| The memorial, shortly after being built. |

|

| And present day. |

Twelve black granite columns were built, to support a grey granite roof that featured striking decorations and a different epigraph on each side. One of these, 'Light evermore', provides a simple, telling summation of what architect and bereaved were trying to convey.

Between the columns, artisan Bertram Mackennal produced a striking white marble sculpture as the centrepiece. The deceased is depicted as she lay before being buried, based on detailed descriptions supplied by Springthorpe, and attended and watched over by angels.

Above the sculpture is, perhaps, the most amazing feature of all; a segmented, lead light roof in different shades of ruby and violet, bathing the memorial in a warm glow.

For the finishing touch, the curator of the Royal Botanic Gardens, William Guilfoyle, was retained to landscape the immediate surrounds. Guilfoyle planted flowering redgums, and other natives, providing a lush green backdrop to the stone memorial structure.

With such grand plans, the construction of the memorial and garden took some time and expense. Construction started in 1899 and did not finish until February 1901 and the final cost, while not formally known, is estimated to have been tens of thousands of pounds, an enormous sum for the day.

But everyone seemed well pleased with the result. The Age called the memorial 'one of the most beautiful... in the Commonwealth.' Although Springthorpe himself would provide a much more romantic description of his realised vision:

Words to consider, if you pay a visit, to this day.