One of the first posts that I made on this blog was a look back at some of the buildings that Melbourne has lost over the years; our stylish architectural heritage that is no more, for a variety of reasons. It's a topic that, sadly, provided a lot of material.

So while I am in Sydney this week it seemed like a good time to revisit the concept, now applied to Australia's largest city. And, as you might expect, there are many more lost wonders to consider. The following is just a sample.

Built in 1890 for a hefty 150 000 pounds, The Metropole was, at the time, considered Sydney's finest hotel. Its 260 rooms were sumptuously furnished, and the public areas were decorated with imported ceramic tiles and stained glass windows. It also featured a rooftop garden, offering views across the city, then something of a novelty. Writers Rudyard Kipling and Jack London were among the notable guests (there is a story that London complained about the hotel staff refusing to provide him with an extra candle). The building was demolished in 1969 to make way for a skyscraper, itself replaced in 1992 with Governor Macquarie Tower.

Founded in England in 1865, the New Zealand Loan & Mercantile Agency was a finance company with offices in Sydney and Melbourne, along with several branches in NZ. The Sydney office pictured above, in a striking Victorian Mannerist building, opened in 1876 (although the picture used is from the 1930's). I was unable to find any information indicating specifically when the building was demolished, although the company merged with Dalgety and Co in 1961, so it is reasonable to assume that they relocated offices at that time. In this case, it also seems likely the building may have been one of many demolished in the redevelopment push of the 1960's. The site today:

So while I am in Sydney this week it seemed like a good time to revisit the concept, now applied to Australia's largest city. And, as you might expect, there are many more lost wonders to consider. The following is just a sample.

THE GARDEN PALACE

Royal Botanic Gardens

|

| A photo of The Palace, shortly after construction. |

|

| A drawing of the opening of the Exhibition. |

Built in 1879 for the Sydney International Exhibition, on high ground in The Domain, the Garden Palace was the harbour city's answer to the Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne (both buildings commenced construction February 1879). Mirroring London's famous Crystal Palace, the hall had a basic cross design, augmented by a 65 metre tall dome on the eastern side. Construction was round the clock - by arc neon lights at night, a first for Australia - and took only 8 months, costing the state Government a monumental 191 000 pounds.

It was described as the grandest building constructed in Australia to that time, and dominated Sydney's skyline.

The exhibition that followed was to prove a runaway success, with more than a million attendees. The displays were fairly modest, but provided a basic showcase of Australian agriculture and industry, with a few exhibits from the US and England providing some international flavour (most of these were re-used at the Melbourne Exhibition the following year). Once the exhibition was over, the building was put to use housing Government records.

|

| An artists impression of the fire. |

In the early hours of September 22, 1882, a nightwatchman on patrol saw smoke coming from the Palace's dome. The alarm was raised, but by the time the fire brigade arrived the largely timber building was already engulfed in flame. The fire burnt out later in the day, leaving almost no remnants of the building behind (and also destroying an estimated 3000 plants, in the adjoining Botanic Gardens). An enquiry was not able to determine the cause of the fire, although there was widespread speculation that it was deliberately lit.

|

| A photo of the aftemath shows the complete destruction of the building. |

This part of the city has been dramatically re-shaped since the late 19th century, but the overlay below gives some idea of where the building would have been positioned on the modern landscape. The second photo shows the corner in the bottom right of the overlay photo.

|

| Overlay of the building on the present site (Source: Sydney Morning Herald) |

|

| The corner today. |

HOTEL METROPOLE

Corner Young, Bent and Phillip Streets

Built in 1890 for a hefty 150 000 pounds, The Metropole was, at the time, considered Sydney's finest hotel. Its 260 rooms were sumptuously furnished, and the public areas were decorated with imported ceramic tiles and stained glass windows. It also featured a rooftop garden, offering views across the city, then something of a novelty. Writers Rudyard Kipling and Jack London were among the notable guests (there is a story that London complained about the hotel staff refusing to provide him with an extra candle). The building was demolished in 1969 to make way for a skyscraper, itself replaced in 1992 with Governor Macquarie Tower.

|

| The CAGA Building was built on the site after the Metropole was demolished. |

|

| Governor Macquarie Tower replaced the CAGA Building in 1992. |

NEW ZEALAND LOAN AND MERCANTILE AGENCY

88 Bridge Street

Founded in England in 1865, the New Zealand Loan & Mercantile Agency was a finance company with offices in Sydney and Melbourne, along with several branches in NZ. The Sydney office pictured above, in a striking Victorian Mannerist building, opened in 1876 (although the picture used is from the 1930's). I was unable to find any information indicating specifically when the building was demolished, although the company merged with Dalgety and Co in 1961, so it is reasonable to assume that they relocated offices at that time. In this case, it also seems likely the building may have been one of many demolished in the redevelopment push of the 1960's. The site today:

AUSTRALIAN BANK OF COMMERCE

367 George Street

The Australian Bank of Commerce was one of many financial institutions fighting for business in Colonial Sydney. Their grand premises above opened in 1884, and was often considered one of Sydney's finest 19th century buildings. The attrition rate for these early banks was enormous, and the Bank of Commerce was absorbed by the much larger English Scottish and Australian Bank (ES & A) in the 1920's. ES & A maintained it's George Street office until 1970, when the company merged with the Australia New Zealand Banking Group. The building was then torn down and replaced with a modern office building, which was restyled into Sydney's Apple store in 2009:

|

| The replacement building from the 1970s. |

|

| The site today. |

THE LIVERPOOL & LONDON GLOBE INSURANCE BUILDING

62 Pitt Street

The building to the left of the above photo (the grand one in the centre is still standing) was the Sydney office of this British firm, which billed itself as the world's largest insurance provider in the late 19th century. The exact date of construction is uncertain, although the company was incorporated in Sydney in 1865. Photos of the original building are also scarce, although the Art Gallery of NSW does have a pencil sketch of it, by J.Watman.

The building was demolished in 1960 and replaced with a more modern office building, which may have fitted the era it was built but now looks horribly dated.

|

| Demolition in progress, January 1960. |

|

| The site today. |

THE COLONIAL MUTUAL ASSOCIATION BUILDING

Corner George & Wynyard Streets

The Colonial Mutual insurance group had a habit of building grand offices for themselves, and their original headquarters in Sydney was no different. Built in 1891, the six story office building was the city's tallest at the time, although it was shortly after superseded. The building was made primarily of sandstone quarried in nearby Pyrmont, with columns of granite imported from Scotland, at great expense. The building also featured modern lifts (still a rarity at this time), and a new kind of fire proofing, which involved the internal metal structures being encased in terra cotta. The building was demolished in 1969 to make way for the rather plain headquarters of the Bank of New Zealand. This building was itself demolished in 2014:

|

| The Bank of New Zealand Building. |

|

| The site again under redevelopment. |

HENRY BULL & CO.

Corner Market and Yorke Streets

Henry Bull was a local boy made good; in 1862 the young merchant married into Sydney's most prestigious family when he took Hannah Hordern as his wife. Hannah was the daughter of Anthony Hordern jr whose father, Anthony sr, had founded the retail company that had made the family fortune. Expanding from domestic wares (see below), by the end of the 19th century the Hordern's were involved in real estate, farming and finance, and family members had been elected to State Parliament, The Henry Bull building was built in 1904, and marked Henry's efforts to strike out on his own. The rather grand building depicted above was actually a warehouse, used for the receipt and dispatch of a variety of goods. The 53 metre tall tower, one of the highest in the city, was used for water storage. The building was demolished in 1973, an age of carnage for buildings of this vintage, and replaced by the bland St Martins Tower:

THE PALACE THEATRE

230 Pitt Street

Designed by Charles Blackhouse and built in 1896, The Palace was a multipurpose venue that had been originally attached to the sprawling Tattersalls Hotel. Government regulation at the time prohibited live venues from selling alcohol - patrons were required to exit a theatre and then re-enter a drinking establishment via a different door - a requirement that the proprietors circumvented by building a tiny laneway between the theatre and the hotel, that customers could step over. Starting with live music, comedy and vaudeville, after World War II The Palace was used primarily as a cinema, although a famous production of 'Who's Afraid of Virginia Wolf?' was also staged there, in 1964. While opulently decorated, The Palace's small capacity, 775 seats, meant it was always a precarious commercial prospect. It was demolished in 1970 as part of a major redevelopment of this block, with the Hilton Hotel group leveling most of it to build a new property. The location today:

THE ROYAL ARCADE

Between George and Pitt Streets

Lost to the same large scale project as The Palace was the Royal Arcade, one of a number of classic Sydney Arcades that are no more (The Strand is the last remaining 19th century example). Designed by Thomas Rowe and built in 1882, The Royal was opened with great fanfare; Premier Henry Parkes presided over the public ceremony, which was followed by an enormous banquet with tables lining the arcade floor. The three story arcade featured high end retail on the ground floor, topped with two floors of offices. Gas lighting was augmented by a glass roof, and the walls were lavishly decorated with hand crafted wood paneling. Retailers were prohibited from displaying goods outside their shops, to preserve the arcade's appearance. When it was demolished in 1970 it was the oldest arcade in Sydney. Where the George Street entrance to the arcade would have been, today:

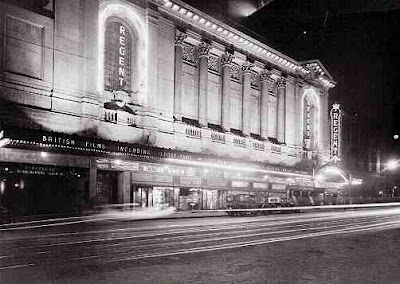

REGENT THEATRE

487 - 503 George Street

Opening in 1928, the 2 297 seat Regent was cinema chain Hoyts' flagship venue in Sydney. The interior was particularly opulent, and the art deco crystal chandelier in the foyer a minor city icon.

In the 1950's the cinema was sold by Hoyts and had several subsequent owners, changing hands every few years. The Regent showed mainstream, first run cinema releases through most of it's life span, but in the 1970's it diversified into live performance; stage musicals, concerts and even opera. By the 1980's The Regent's final owners, the Fink family, had decided to close the theatre and sell the property (the final session was a screening of the documentary 'Ski Time', in May 1984).

|

| The Regent; closed and awaiting its fate. |

But the State Government had placed a temporary development ban on the property while its heritage value was assessed. This turned into a protracted court battle, lasting more than 4 years, while a public campaign was mounted to try and save the building. During this limbo period, the building stood empty and gradually fell into disrepair. When the development ban was finally lifted in 1988, the poor condition of the property was one of the reasons cited. The Regent was finally demolished later that year.

Incredibly, a slump in the Sydney property market then meant that the newly vacant land went undeveloped for more than 15 years! A new commercial property was finally built on the site in 2004:

PALACE EMPORIUM

Corner George and Liverpool Streets

And here we return to the Hordern family, and specifically their remarkable department store in central Sydney. Patriarch Anthony Hordern traveled to America in 1878 and, impressed by what he had seen there, returned to Australia determined to dramatically expand his operations. The enormous Palace Emporium was one expression of this desire. The first Emporium was built in 1879 but, when this burnt down in 1901, Hordern's heirs (Anthony passed away in 1886) simply rebuilt in even grander style. The Palace Emporium filled an entire city block, and was one of the largest department stores in the world.

|

| The original Palace Emporium. |

|

| After the original building burnt down. |

But in the second half of the 20th century, the Hordern's business fortunes began to wane. Increasing competition, and the popularity of American style mall shopping in the suburbs, pushed the company's city retail chain into the red. In the late 1960's Hordern's shops were sold off; most of them taken over by the retail chain 'Walton's' (itself now defunct), while some were bought by smaller chains and independent operators.

|

| The Emporium site, after demolition. |

The Palace Emporium was demolished in the 1980's to make way for the 'World Square' development, a much delayed project worthy of its own discussion. After multiple changes of developer, much government intervention, and two decades of intermittent construction, World Square finally opened in 2004: